The Power of the Vagus Nerve: Renewal, Regeneration, and Connection

The vagus nerve is, without question, one of the most powerful and influential forces in our life. It affects our mood, how we engage with others, our anxiety level, digestion, sleep, and how well we recover from illness, accident, stroke, and brain injury. Strong “vagal tone,” can improve overall health, physical stability, emotional balance, flexibility and adaptability, recovery and regeneration after shock and trauma, and our ability to connect and engage with others.

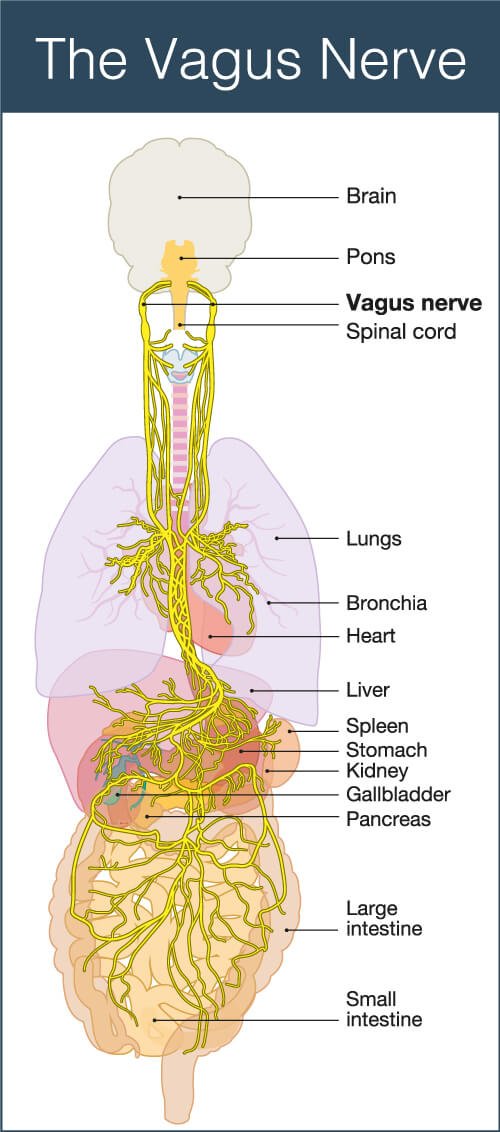

The vagus nerve is the 10th cranial nerve and the longest nerve in the body. It’s the only cranial nerve that extends beyond the head and neck area, reaching all the way to the gut. The word vagus is Latin for “wandering,” which is an apt description. The vagus nerve is actually a pair of nerves that emerge from the top of the brain stem and, after leaving the skull, enter the upper neck area behind the ears. It then passes down through the neck to the throat and vocal chords to the heart, lungs, stomach, liver, kidney, spleen, gallbladder, and pancreas, and finally to the small intestine and part of the large intestine. As it travels through the body, the vagus nerve regulates swallowing, vocalization, breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, immune responses, and the microbiome of our intestines.

The Polyvagal Theory

The Polyvagal Theory was introduced in 1994 by Dr. Stephen Porges, Distinguished University Scientist at Indiana University. It explains the inter-relationship of the vagus nerve and the autonomic nervous system; how this collection of nerve pathways work together to respond to our environment; and why it underlies all of our behavior, thoughts, and feelings. The vagus nerve has two branches that communicate with the autonomic nervous system, which has three branches: the sympathetic (flight/flight), parasympathetic (rest/restore), and enteric (digestion/elimination). While this is a complex theory let’s look at the vagus nerve in more general terms in relation to physical stability and balance, emotional equilibrium, speech and vocalization, recovery from stroke and brain injury, coordination, anxiety, and post traumatic stress symptoms.

How it Functions

“Healthy vagal tone can be thought of as an optimal balance of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system actions that allows you to respond with resilience to the ups and downs of life.”

The vagus nerve provides a direct link between the body and the brain through a two-way communication system: 80% of the neural signals go from the body to the brain to tell the brain what is going on inside the body; 20% go from the brain to the body to regulate the organs, blood flow, and muscles. It is continuously receiving and sending signals it picks up from inside the body, outside the body (our environment), and between people – we actually pick up on the energy of another person’s nervous system. It’s like an antenna running the length of the body that is always “on” and listening for signals that indicate danger or safety. The vagus nerve, working in conjunction with the autonomic nervous system, initiates our response to these ‘fight or flight’ signals. Do we go into a protective, withdrawn, shut down mode or an open, receptive, connecting mode?

We function best when we can move easily between these two systems – being cautious while scanning our environment yet having easy access to a relaxed, flexible state.

Physical Stability & Emotional Balance

The vagus nerve and its associated nerve networks underlie our awareness of our environment: knowing where we are in space, balance and hearing, how we move, stability as we walk, and whether or not we can maintain an erect posture. When the vagus nerve sends signals to our sympathetic system that there is a danger or threat, we respond by withdrawing. Our focus narrows to pay attention to the danger that may be imminent, our heart rate speeds up, blood flow to the muscles increases, the enteric nervous system (the mesh-like system of nerve-nets that govern the gastrointestinal tract) shuts down, the pupils of the eyes dilate, and breathing becomes rapid. We are in the fight/flight mode and cannot pay attention to the things around us nor can we move fluidly and smoothly.

In the Brain Gym® model, we associate this dynamic with the Focus Dimension – the front and back of the body (forebrain and brain stem). When we are “switched off” in this dimension, we do not have the ability to be aware of the environment around us while at the same time focusing on something specific, such as the stairs we are navigating, the person with whom we are speaking, the book we are reading, or any specific task. Read more about the Focus Dimension and its role in The Three Dimensions of Movement.

I have worked with many survivors of abuse and trauma whose bodies are locked into the sympathetic fear response. They generally have poor balance, are disengaged from life, and are anxious, rigid, and experience post-traumatic stress symptoms. As Brain Gym movements and related techniques “switch on” the Focus Dimension, balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems is re-established and the frozen, clinched muscles release, freeing the person to breathe and move more easily. They relax, connect with their emotional selves, are more flexible and stable in their movements, experience an easy, erect energy, and are able to participate more fully in life.

Speech & Vocalization

The vagus nerve connects to areas of the throat that influence speech, vocalization (any sound we make), and the pitch of our voice. It delivers motor signals to the muscles that control swallowing and the opening and closing of the upper airway which is necessary for speech. From here the vagus nerve continues downward to the larynx, our “voice box,” controlling muscles above and below the vocal cords. The vagus nerve then travels down to the lungs where it controls the opening and closing of the bronchi – the two large tube-like structures that carry air from the throat to the lungs. Vagus nerve fibers extend into the lungs to open and close the bronchi as we breathe. It’s important to note that we use the air from our lungs in coordination with the vocal cords for all sounds that we make.

In addition, the neural circuits of the vagus nerve that regulate the internal organs of the chest and abdomen are linked to the nerves that regulate and tone the middle ear structures (see Integrated Listening Systems,1). When the vagus nerve is toned and active we are able to process auditory input more easily and we can hear better – our own speech and the words of others.

Using a variety of techniques to tone the vagus nerve in the throat, vocal cords, and chest during the rehabilitation process has proven helpful for some people who struggle with speech after a stroke.

Recovery from Brain Injury

A healthy vagus nerve is important for brain injury survivors. Due to its extensive nerve network and coordination of bodily responses, it has a direct influence on inflammatory responses, including the inflammation from injuries to the brain.

“Stimulating the vagus nerve encourages the brain to reorganize itself around damaged areas.”

Dr. Datis Kharrazian, Ph.D, Harvard Medical School research scientist, has researched brain injury extensively and he lists neuroinflammation in the brain, loss of brain integration, and “impaired vagal motor activity” as some of the many consequences of brain injury. He connects all of these to gastro-intestinal dysfunction (see Kharrazian), as the vagus nerve is intimately connected to the intestines through its activation of the enteric nervous system. Toning and strengthening the vagus nerve directly improves the functioning of the gastrointestinal tract, which in turn improves brain function. Remember that 80% of the vagus nerve communication that goes from the gut to the brain – there is a direct link between a healthy gut and a well-functioning brain.

In Summary

What we are currently learning about the vagus nerve and its association with the autonomic nervous system is revolutionary. It is providing us with a new understanding of emotional dysfunction, physical ailments, and mental confusion. As we look more deeply into the relationship of the vagus nerve and the autonomic nervous system we are discovering new possibilities to develop innovative approaches for issues such as depression, anxiety, speech impairment, hearing issues, brain injury, and physical balance and stability. As physicians, counselors, therapists, body-workers, and energy healers begin to incorporate this knowledge into their practices, the future looks bright for many who suffer from chronic, difficult to diagnose, or obscure ailments.

Activate & Tone Your Vagus Nerve

It doesn’t take too much effort to activate and tone your vagus nerve. Try the Self Massage or click to explore a few other suggestions, or consider committing to one for a week and make note of how you feel.

Self Massage

As the vagus nerve is closest to the surface of the body at the ears, I have developed this self-massage that you may find very relaxing.

Figure 1

Massage the outer edges of the ears from top to bottom several times.

Rub behind the ears for about 30 seconds.

Place your hands as shown in Figure 1 and stroke down the sides of the neck, 8 to 10 times.

Gently squeeze/pinch the sides of your neck, alternating sides, 10 to 15 times.

Place your hands, one on top of the other, on your chest and gently massage in a circular motion in either direction. Continue for as long as you wish.

Place your hands flat against the sides of your body and with a firm pressure stroke toward the front of your body, 8 to 10 times.

Place your hands on your belly and breathe slowly and deeply into your belly cavity (vs. your chest). Breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth.

Massage your belly in a circular, clockwise motion around and down to your left. Continue for as long as you wish.

Finish by closing your eyes, breathe comfortably, and notice the changes in your body and your mental state.

-

If you are familiar with Brain Gym, the movements listed correspond to techniques that activate and tone the vagus nerve. If Brain Gym is unfamiliar to you, please contact me for information about this remarkable program of designed movement techniques for optimal performance in all aspects of life.

1. Neck Rolls

2. The Thinking Cap

3. Belly Breathing

4. Balance Buttons

5. Brain Buttons

6. The Energy Yawn

7. The Owl -

The vagus nerve is connected to your vocal cords tongue, throat, and muscles of the neck. Dr. Lin (see Lin, Dr. Steven), a functional dentist, suggests the following:

• Breathe through your nose, which allows the vagus nerve to be stimulated, rather than through your mouth, which inhibits activation of the vagus nerve.

• Suck your tongue to the roof of your mouth and toward the back of your throat. Hold for 20 seconds, rest. Repeat five times.

• Take a few moments to sing, hum, gargle, laugh, or chant on a daily basis. -

• Splash cold water on your face three times a day. The vagus nerve functions in conjunction with four cranial nerves serving the face and neck: trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, and the accessory nerve.

• Take a cold shower or turn the water to cool/cold at the end of your shower.

• Include probiotics in your diet to improve the microbiome of the gut, which directly affects the brain through the vagus nerve’s gut/brain connection.

• Sign up for classes in Yoga, QiGong, or meditation. It is well known that these practices are calming to the nervous system.

The views expressed in this article belong solely to S. Christina Boyd based on 30 years of clinical experience as a movement therapist. If you would like further reading, please explore the source and related information provided.

-

Kharrazian, Datis Ph.D, Traumatic Brain Injury Mechanisms of Gastrointestinal Tract

Integrated Listening Systems,1, How Much Can A Nerve Running From The Brain To The Stomach Affect How You Feel

Integrated Listening Systems Quote, Vagus Nerve Stimulation Aids Stroke Recovery

Schwartz, Dr. Arielle Quote, Licensed Clinical Psychologist

Rosenberg, Stanley. Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, CA 2017. Chapter Two provides an excellent explanation of Porges’ Polyvagal Theory.

Porges, Dr. Stephen. Interview with Randall Redfield. Integrated Listening Systems, February 16, 2017. Dr. Porges discusses his Polyvagal Theory and the Social Engagement System.

Habib, Dr. Navaz. Activate Your Vagus Nerve, Unleash Your Body’s Natural Ability to Heal. Ulysses Press, Brooklyn, NY 2019. Provides a detailed description of the pathways and function of the vagus nerve.

Vagus Nerve and Brain Injury. Hope After Brain Injury

Vagus Nerve: Location, Branches and Function. Kenhub GmbH, Learn Human Anatomy (YouTube), July 2018. -

Lin, Dr. Steven, The Functional Dentist

Integrated Listening Systems, Polyvagal Theory: The Science of Feeling Safe

Vagal Stimulation Modulates Inflammation Through A Ghrelin Mediated Mechanism In Traumatic Brain Injury. Bansal, Vishal, et al. National Library of Medicines, February 2012.

The Vagus Nerve in the Neuro-Immune Axis: Implications in the Pathology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Bonaz, Bruno, et al. Frontiers in Immunology, November 2017.

MacKay, Karen and Marcovici, Lisa. Brain Gym & the Polyvagal Theory – An Introduction. Podcast, June 2021. Contact Breakthroughs International for information.

Deb Dana Describes the Polyvagal Theory. Norton Mental Health (YouTube), March 2020. Deb Dana is Coordinator of the Traumatic Stress Research Consortium in the Kinsey Institute

Dana, Deb. “What Therapists Need to Know About Polyvagal Theory.” Interview by Lauren Dockett, Psychotherapy Networker, May 2019.

Rigoni, Dr. Carrie. Vagus Nerve Toning: A Path to Physical and Mental Wellbeing. Website Blog, Dr.CarrieRigoni.com.au, May 2020.

Smith, Dr. Melanie. Discover Your Vagus Nerve as an Energetic Healing Pathway to Optimal Wellbeing. Interview by Cari Hernandez, The Shift Network, August 2021.

Putting It All Together: The Nervous System and the Endocrine System. Chapter 4.4, Introduction to Psychology. OpenText BC (Canada)